|

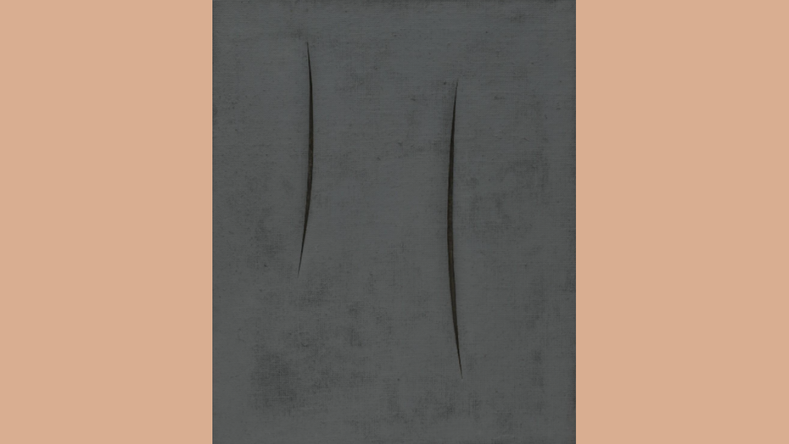

ELIZABETH BERNHARDT, PHD Born and raised in St. Louis, Vaughn Davis Jr. (b. 1995) grew up with art in his family: his grandmother makes things and decorates in eclectic ways and his father has always been great at drawing. Vaughn began along these same family lines and then worked toward a formal art degree: he received his BFA in Sculpture (with honors) from Webster University. Vaughn begins his work like most painters. He mixes colors and paints on canvas, and he often uses traditional tints that would have appealed to Old Masters: reds, blues, yellows, greens, etc. But unlike many of the great old-schoolers, Vaughn likes to paint the canvases when they are wet so that the pigments bleed and expand into one another. He also likes to paint both sides of his canvas. Continuing work against the centuries-old European tradition fixed in guild rules and regulations, Vaughn continues his deconstruction process in numerous fashions. He uses canvas free from frames so his work does not reference fixed squares "trapped" in frames (like most art employing the use of canvas). He distresses the loose painted canvas itself with the help of knives, scissors, blades and his own two hands. He cuts, tears, rips, smushes and warps his canvases yet without ever removing any element of the canvas; so if his canvases were flattened out, they would be intact and whole. He explains that his art is a reaction to the past, a reaction to the Classics; it is an art of protest. Vaughn makes these painted and ripped canvases turn into 3D sculptures that detest restraint. He explains that he rips and tears in order to "open up" the canvas, to release flatness and to free them. They really do appear free. He explains that the deconstruction process signifies the search and the opening up of the self. Along these lines, I watched him tear some of his work that had already been hung in the gallery; he said that even the sound of the canvas ripping is therapeutic. The final products appear to be paintings and sculptures “in one.” Furthermore, his works are in movement in the sense that they are able to evolve. Each time they are moved, the pieces takes on new forms, curves and shapes depending on how they are hung—and because they become so different each time they are displayed, Vaughn has even given them different titles as they transform themselves in different locations. He calls it freestyle work. It is fascinating to think that canvas has been used by artists for about 500 years now. Canvas was popularised by Venetian painters in the Cinquecento (like Paolo Veronese (1528-1588) in his controversial and enormous painting, Feast in the House of Levi), and the use of it spread across Europe and through the art world. In Venice, canvas—made from weaving strands of the strong and resistant canapa plant—was grown on the terraferma, woven locally, and readily available to sailors for their ship sails but later adopted by practical painters for large-scale compositions. Canvas weighs a lot less than wood panel, it does not warp like wood in the intense local humidity, it is easier to move around than panel since it can be rolled up, it costs less than panel, and it does not fall off of walls like wet plaster or frescoes does in homes built in water around a lagoon. It is fascinating to see Vaughn, a 21st c. artist from St. Louis, take up this same historical material in his work. Veronese’s canvas, commissioned to represent the Last Supper, got him in trouble with the Inquisition because of so many real-life details added to it: gluttons, drunkards, wealthy patricians, German Protestant soldiers, sleeping cats and dogs, dwarves, servants, a man with a bloody nose, and other elements potentially present at an aristocratic dinner party—things thoroughly extraneous to a more traditional depiction of the Last Supper. Veronese’s canvas is therefore tied to real life and to a rebellious artistic nature. In different fashions, Vaughn’s canvas is tied to those two same concepts. Vaughn’s work is also related to that of Sam Gilliam (b. 1933) who has painted enormous colourful canvases and hung them in liberating ways. Gilliam’s canvases stand as sculptures yet they are often more regularly patterned and formed when compared to Vaughn’s pieces. Vaughn’s work also recalls the famous slit-up canvases of Lucio Fontana (1899-1968) who was born in Argentina but returned to Italia where he helped deconstruct the centuries-old traditions behind Italian painting. Fontana sought to escape the “prison” of the flat picture surface to explore movement, time, and space. Vaughn sometimes begins to cut like Fontana yet goes a step further with irregular ripping, shaping and installing. Vaughn is also related to the Gutai group (具体美術協会) of post-war Japanese artists whose experimental work is deeply tied to freedom and liberation. This 1950s group focused on experimentation, on performance, and on liberating color—while Vaughn has found a slightly different path as he focuses on liberating the canvas from itself.

Lastly, Vaughn’s work distantly recalls another of Italy’s greatest artists and social protestors: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610). Caravaggio loved pushing his canvases to the limit—although in his time pushing them beyond the acceptable norm often meant depicting intense and crude realism; a great example comes to mind in his Death of the Virgin now in the Louvre. Veronese and Caravaggio—among all artists who have employed canvas as their medium of choice—would be fascinated to see how Vaughn uses and liberates canvas—and the early modern Italians who used it might also be fascinated to learn that canvas remains popular with artists into the 21st century. Vaughn has had a lot of experience doing different things—although he is a mere 25 years old. He has worked in clothing stores and at a coffee house, he studied abroad in Vienna and is considering an MFA at the Royal College of London. He plays the trumpet and is a professional art handler. He likes to go cruising around St. Louis neighbourhoods on his longboard. He is part of a “Philadelphia model” gallery called Monaco on Cherokee Street. Into the future, will he continue a deconstruction process related to the use of canvas and/or painting? Will he continue to deconstruct art before perhaps re-constructing it from scratch? Will he continue to create pieces that cross genres and remain simultaneously paintings and sculptures? He has an exciting open road ahead.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsGiovanna Leopardi Year

All

Archives

July 2024

|

|

Contact us:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed